Disproportionality Analysis

Contemporary drug postmarketing surveillance largely relies on the collection of spontaneous reports of suspected adverse drug events from pharmaceutical companies, healthcare professionals, and patients. These reports are curated and stored in spontaneous reporting systems (SRS), usually organized as a large frequency table for downstream data analysis. We consider an SRS dataset cataloging AE reports on AE rows across drug columns. Let denote the number of reported cases for the -th AE and the -th drug, where and . Therefore, AE-drug pairwise occurrences from the AE-reports are summarized into an contingency table, where the -th cell catalogs the observed count indicating the number of cases involving -th AE and the -th drug.

Current disproportionality analysis mainly focuses on signal detection which seeks to determine whether the observation is substantially greater than the corresponding null baseline . Or equivalently, its signal strength is significantly greater than 1.

In addition to signal detection, Tan et al. (Stat. in Med., 2025) broaden the role of disproportionality to signal strength estimation. The use of the flexible non-parametric empirical Bayes models enables more nuanced empirical Bayes posterior inference (signal strength estimation and uncertainty quantification). This allows researchers to distinguish AE-drug pairs that would appear similar under a binary signal detection framework. For example, the AE-drug pairs with signal strengths of 1.5 and 4.0 could both be significantly greater than 1 and detected as a signal. Such differences in signal strength may have distinct implications in medical and clinical contexts.

Methods implemented in this package assumes the observed count conditional on is that where the parameter is the relative reporting ratio, the signal strength, for the -th pair measuring the ratio of the actual expected count arising due to dependence to the null baseline expected count. Therefore, are our key parameters of interest. A large indicates a strong association between a drug and an AE.

Let be a prior density function for signal strength parameters for all AE-drug pairs: . Then, in the context of the Poisson model, the marginal probability mass function of is given by: where is the probability mass function of a Poisson random variable with mean evaluated at . Under the empirical Bayes framework, the prior distribution is consequently estimated from the data by maximizing the log marginal likelihood: Then, the estimated empirical Bayes posterior density of given is: where .

All empirical Bayes models implemented in ‘pvEBayes’ share the structure described above; they differ by their assumptions on the prior distribution. Implemented methods include the Gamma-Poisson Shrinker (GPS), Koenker-Mizera (KM) method, Efron’s nonparametric empirical Bayes approach, the K-gamma model, and the general-gamma model. The selection of the prior distribution is critical in Bayesian analysis. The GPS model uses a gamma mixture prior by assuming the signal/non-signal structure in SRS data. However, in real-world setting, signal strengths are often heterogeneous and thus follows a multi-modal distribution, making it difficult to assume a parametric prior. Non-parametric empirical Bayes models (KM, Efron, K-gamma and general-gamma) address this challenge by utilizing a flexible prior with a general mixture form and estimating the prior distribution in a data-driven way.

The KM method has an existing implementation in the

REBayes package, but it relies on Mosek, a commercial

convex optimization solver, which may limit accessibility due to

licensing issues. The pvEBayes package provides an

alternative fully open-source implementation of the KM method using

CVXR. Efron’s method also has a general nonparametric

empirical Bayes implementation in the deconvolveR package;

however, that implementation does not support an exposure or offset

parameter in the Poisson model, which corresponds to the expected null

value

.

In pvEBayes, the implementation of Efron’s method is

adapted and modified from deconvolveR to support

in the Poisson model. In addition, this package implements the novel

bi-level Expectation Conditional Maximization (ECM) algorithm proposed

by Tan et al. (2025) for efficient parameter estimation in gamma mixture

prior based models mentioned above.

Package ‘pvEBayes’ provides a suite of streamlined tools for effectively fitting these models to the spontaneous reporting system (SRS) frequency tables, extracting summaries, performing hyperparameter tuning, and generating graphical summaries (eye plots and heatmaps) for signal detection and estimation. In the following we provide an example, borrowed from Tan et al. (arxiv, 2025), of SRS data analyzing with ‘pvEBayes’.

Analyzing FDA statin SRS data with pvEBayes

library(pvEBayes)

library(ggplot2)

# load the SRS data

data("statin2025_44")

# show the first 6 rows

head(statin2025_44)

#> Atorvastatin Fluvastatin Lovastatin

#> ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY 1132 23 23

#> ANURIA 46 0 0

#> BLOOD CALCIUM DECREASED 51 2 0

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE ABNORMAL 19 0 0

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE INCREASED 624 21 4

#> BLOOD CREATININE ABNORMAL 11 0 0

#> Pravastatin Rosuvastatin Simvastatin

#> ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY 153 1141 453

#> ANURIA 1 56 29

#> BLOOD CALCIUM DECREASED 3 877 6

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE ABNORMAL 0 11 1

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE INCREASED 41 557 216

#> BLOOD CREATININE ABNORMAL 0 32 6

#> Other_drugs

#> ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY 192114

#> ANURIA 7079

#> BLOOD CALCIUM DECREASED 33175

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE ABNORMAL 133

#> BLOOD CREATINE PHOSPHOKINASE INCREASED 17203

#> BLOOD CREATININE ABNORMAL 2645Fit the general-gamma model

Our interest lies in finding the most important adverse events and estimating the corresponding signal strength of these 6 statin drugs. These are achieved by fitting empirical Bayes models with pvEBayes() to the SRS data. We begin by fitting the general-gamma model to this dataset. Other models mentioned above could be used by modifying the ‘model’ argument. For illustration, we fit the model with a fixed hyperparameter value of $ = 0.5$ using the pvEBayes() function.

gg_given_alpha <- pvEBayes(statin2025_44,

model = "general-gamma",

alpha = 0.5

)

gg_given_alpha_detected_signal <- summary(gg_given_alpha,

return = "detected signal"

)

sum(gg_given_alpha_detected_signal)

#> [1] 105The return argument specifies which component the summary function should return. Valid options include: “prior parameters”, “likelihood”, “detected signal”, and “posterior draws”. If it is set to NULL (default), all components will be returned in a list. In this example, we show the detected signals.

In this package, we suggest tuning the general-gamma model by AIC or BIC, which can be accessed through ‘AIC()’ or ‘BIC()’ functions, as shown below:

In practice, one can specify a list of candidate values, fit the general-gamma model for each, compute the corresponding AIC or BIC, and select the model with the lowest AIC or BIC. Instead of manually doing so, one can use the ‘pvEBayes_tune()’ function, which implements these steps. The relevant code is given below:

gg_tune_statin44 <- pvEBayes_tune(statin2025_44,

model = "general-gamma",

alpha_vec = c(0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9),

use_AIC = TRUE

)

#> The alpha value selected under AIC is 0.5,

#> The alpha value selected under BIC is 0.

#> alpha AIC BIC num_mixture

#> 1 0.0 3803.082 3960.690 14

#> 2 0.1 3799.012 3990.393 17

#> 3 0.3 3798.874 4001.513 18

#> 4 0.5 3796.813 3999.452 18

#> 5 0.7 3824.280 4083.208 23

#> 6 0.9 3912.529 4340.322 38Visualization

In addition, ‘pvEBayes’ has implemented visual summary methods for both signal detection and estimation, which are heatmap and eyeplot. These plot functions can be accessed through the ‘plot()’ with argument type = “heatmap” or type = “eyeplot”.

heatmap_gg_tune_statin44 <- plot(gg_tune_statin44,

type = "heatmap",

num_top_AEs = 10,

cutoff_signal = 1.001

)

heatmap_gg_tune_statin44 +

theme(

legend.position = "top"

)

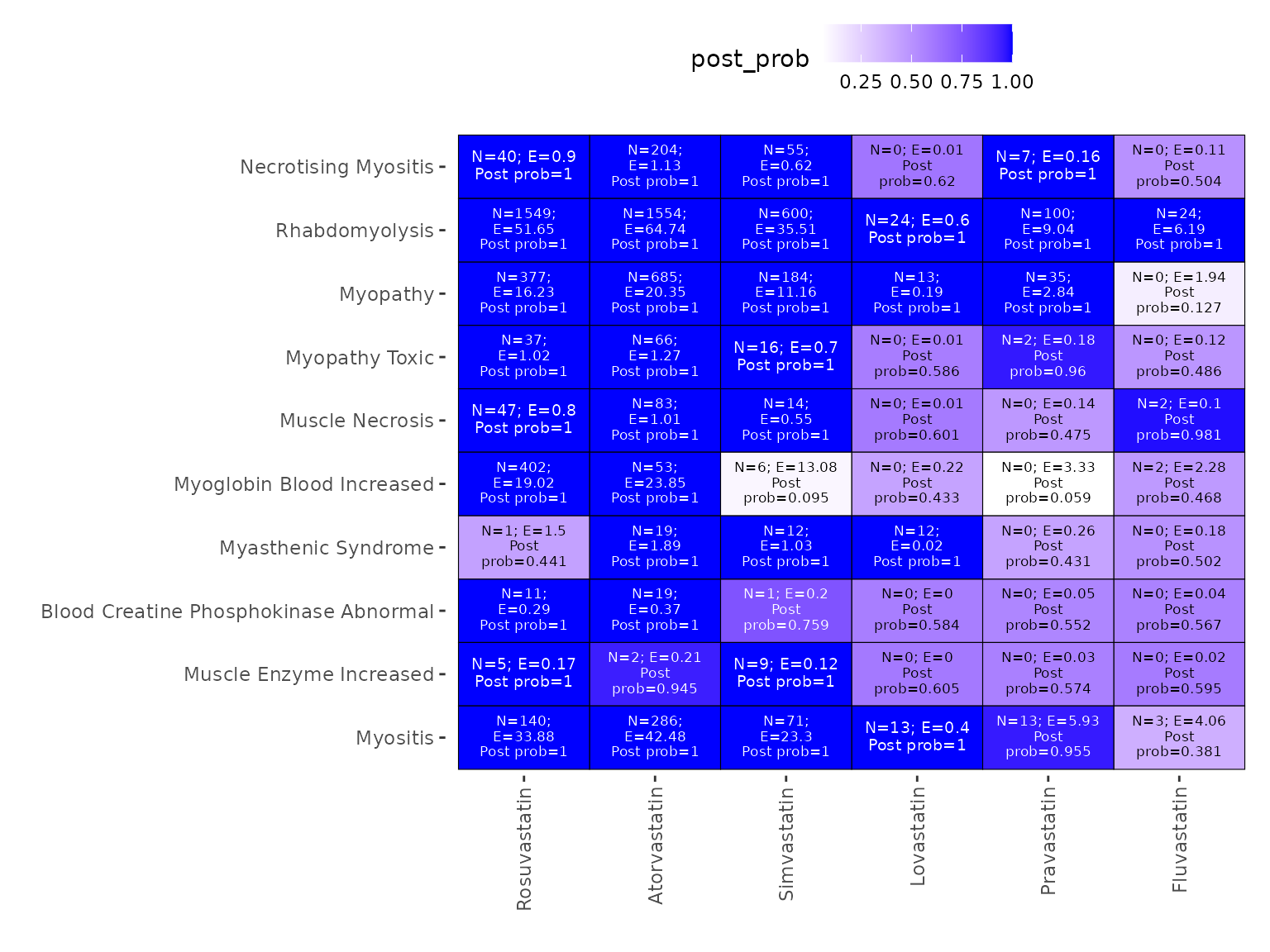

The above heatmap visualizes the signal detection result for the fitted general-gamma model. For each AE-drug combination, the number of reports (N), the estimated null value (E), and the estimated empirical Bayes posterior probability of being a signal are given. A deeper blue color indicates stronger evidence for a signal.

eyeplot_gg_tune_statin44 <- plot(gg_tune_statin44,

type = "eyeplot",

num_top_AEs = 8,

N_threshold = 1,

log_scale = FALSE,

text_shift = 2.3,

text_size = 3,

x_lim_scalar = 1.2

)

eyeplot_gg_tune_statin44 +

theme(

legend.position = "top"

)

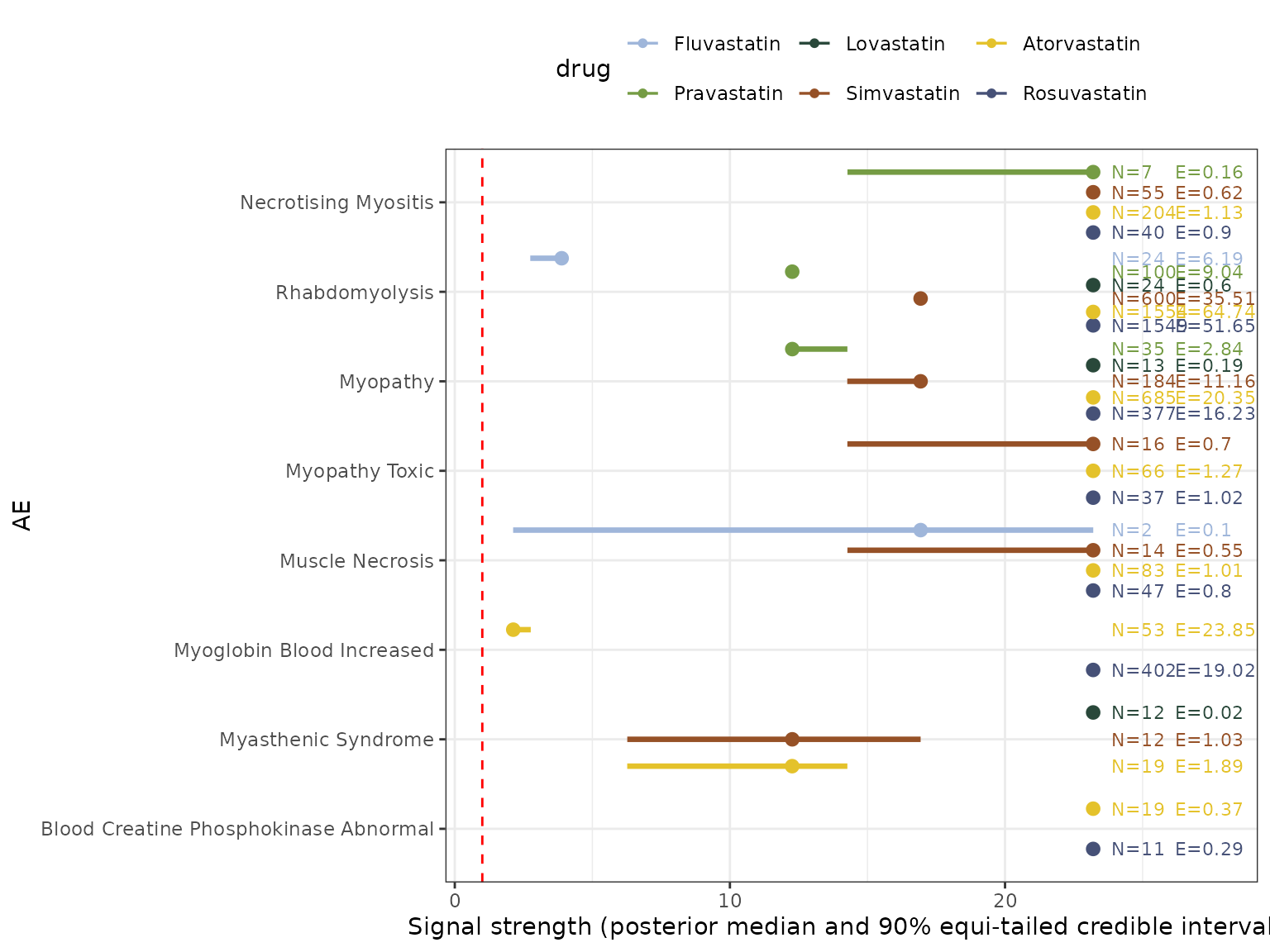

The above eyeplot visualizes empirical posterior inferences on 10 prominent AEs across 6 statin drugs through computed empirical Bayesian posterior distributions of signal strengths obtained from the general-gamma model fitted on the statin2025_44 dataset. The points and bars represent the posterior medians and 90% equi-tailed credible intervals for the corresponding AE-drug pair specific , with different colors indicating the results from different statin drugs. The red dotted vertical line represents the value ‘1’. The texts on the right provide the number of observations as well as the null baseline expected counts under independence for an AE-drug pair.

References

Tan Y, Markatou M and Chakraborty S. Flexible Empirical Bayesian Approaches to Pharmacovigilance for Simultaneous Signal Detection and Signal Strength Estimation in Spontaneous Reporting Systems Data. Statistics in Medicine. 2025; 44: 18-19, https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.70195.

Tan Y, Markatou M and Chakraborty S. pvEBayes: An R Package for Empirical Bayes Methods in Pharmacovigilance. arXiv:2512.01057 (stat.AP). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2512.01057

Koenker R, Mizera I. Convex Optimization, Shape Constraints, Compound Decisions, and Empirical Bayes Rules. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2014; 109(506): 674–685, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2013.869224

Efron B. Empirical Bayes Deconvolution Estimates. Biometrika 2016; 103(1); 1-20, https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asv068

DuMouchel W. Bayesian data mining in large frequency tables, with an application to the FDA spontaneous reporting system. The American Statistician. 1999; 1;53(3):177-90.